Writing

-

No Wheels, No Problem: How to Experience Los Angeles without a Car

By Andrea Gutierrez » Originally published on OnSheGoes.com (August 16, 2017) I hate driving. It’s not just the traffic or the amount of money I’ve sunk into the most basic upkeep of owning a car—I hate the act of driving. And yet I drive every day, usually alone, through clogged streets and freeways, another lone driver…

-

We Were Angry and Wanted an Outlet: Hijas de la Paz

by Andrea Gutierrez » Originally published in make/shift (Summer/Fall 2017, no. 20) When Michelle Lozano and Bree’Anna Guzman, two young women from Los Angeles’s Lincoln Heights neighborhood, were murdered within months of each other in 2011 and 2012, sisters Selena Ortega and Adriana Duran knew they had to act. They didn’t know the murdered women, but they…

-

How to Grow Old

by Andrea Gutierrez » Originally published in issue 6 of Huizache (Fall 2016) Grandma’s preparations for her death began in 1975, some years before I was born. Grandpa Roland had just died of a heart attack while golfing in Griffith Park, and she made funeral arrangements at Mirabal Mortuary near her house in Lincoln Heights—not only for…

-

Film Review: Don’t Tell Anyone (No le digas a nadie)

By Andrea Gutierrez » Originally published in Bitch (Summer 2016, no. 71) Don’t Tell Anyone (No le digas a nadie) Director: Mikaela Shwer Portret Films “No le digas a nadie,” Angy Rivera’s mother would warn her about their undocumented immigration status. Don’t tell anyone. In the documentary of the same name, Angy Rivera chafes against this advice…

-

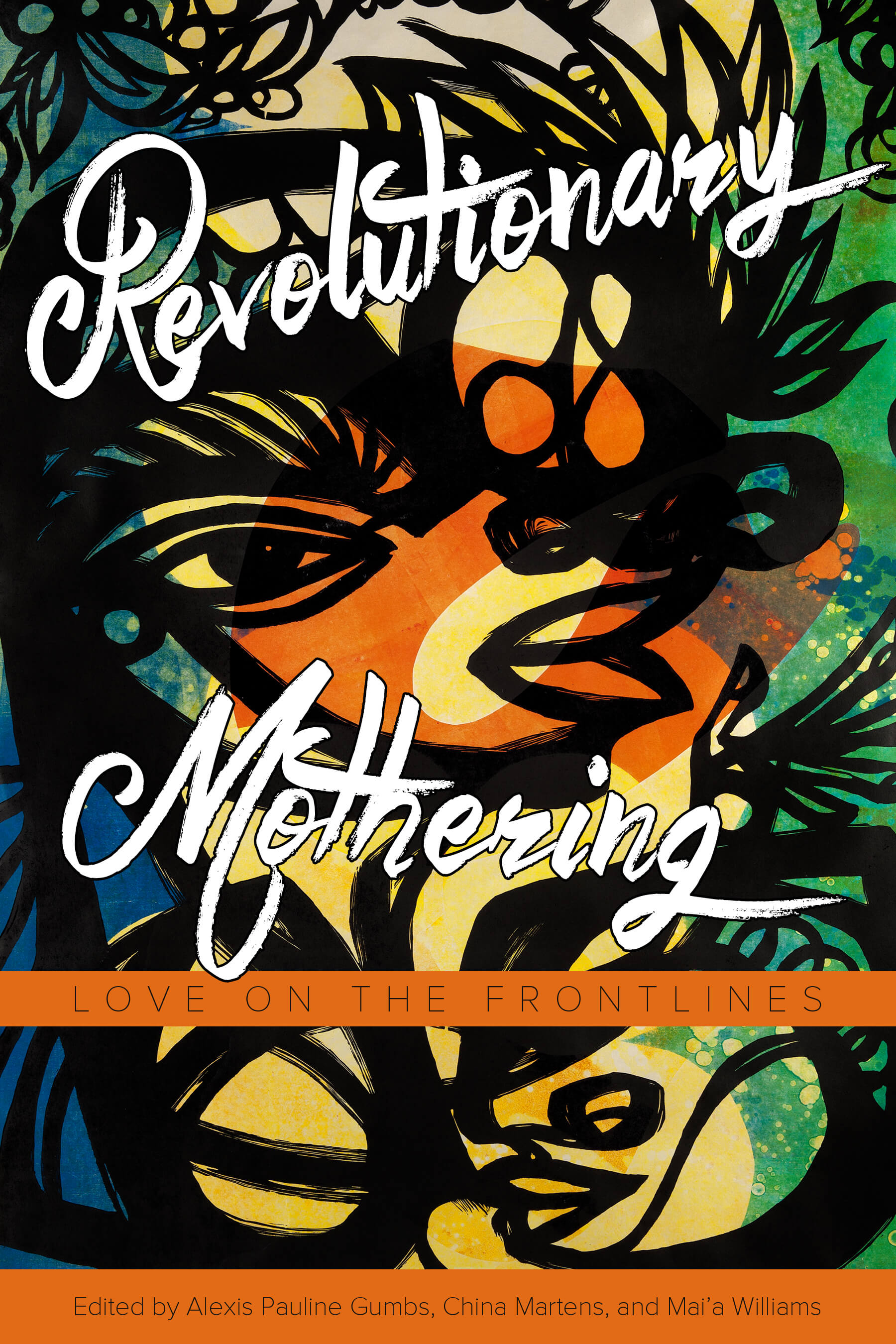

Love on the Front Lines: A Roundtable with Co-Editors of Revolutionary Mothering

By Andrea M. Gutierrez » Originally published in make/shift (Summer/Fall 2016, no. 19) Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines (PM Press), co-edited by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams, is an anthology that centers and celebrates mothers and acts of mothering in marginalized communities, in particular radical mothers of color. Prose and poems make…